Lunar Impacts Research

| Riga 3: | Riga 3: | ||

==== ==== | ==== ==== | ||

| − | <br>This is new programme that has been started by the Lunar Section Research of Unione Astrofili Italiani (UAI), and consists of monitoring the Moon’s night side for Impact flashes that occur when meteoroids, in the Solar System, strike the lunar surface at high velocity. The research on Lunar Impacts started only recently, when on November 18, 1999, the orbit of the Earth-Moon system intersected the Leonids meteor shower orbit. On that date, Brian Cudnik was the first person to observe this phenomena visually, through his telescope, i.e. the flash of light when one object in the solar system collides with the surface of another, and this event was confirmed, and recorded on video, by other independent lunar observers. After this first impact flash, there followed in succession six other impact flashes, always confirmed by independent observers, and this opened up a new scientific way to carry out research into impact rates on our natural satellite. This type of programme is important scientifically for a number of reasons, for example if we measure the brightness of the flash and compare it to that of stars near to the limb of the Moon, then we can obtain the magnitude of the flash, and from this determine the emitted energy of the impact. If the meteoroid is from a known shower, and of known velocity, then its mass can be calculated too.<br> This study can be very useful in detemining the quantity of “minor bodies” that pass near to the Earth, and to calibrate this with other methods, for example meteor/meteorite rates detected in the Earth’s atmosphere. The programme could have a really important scientific significance for future lunar exploration too, i.e. to be able to know the present day lunar impact rate and how this varies across the lunar surface would be essential to know about in the design of future lunar bases, and also where they should be situated, in order to minimize impact damage. <br><br>The mass of meteoroids that fall on lunar surface can vary between some tens of grams and many hundreds of kilograms, while the velocity of impact is between 20 and 72 km/second. These meteoroids can originate from cometary showers that periodically cross the orbit of the Earth-Moon system, or from asteroidal bodies that are more sporadic in nature, and it is this second case that the mass of meteoroids have more significance to the safe design of lunar bases. In the instance immediately after an impact, less than one percent of the total kinetic energy released from the impact, is transformed into visible light that Earth based observers can see in the form of short flashes. These flashes can last from typically less than 1/10th of a second to very occasionally a few seconds for the largest bodies to hit the Moon. After the impact the meteoroid disintegrates and a new, metre scale, crater forms. <br>The UAI Lunar Section undertakes this research programme in collaboration with the [http://www.nasa.gov/centers/marshall/news/lunar/ NASA Marshall Space Flight Center] who, at professional level, catalogue all observations of Lunar Impacts provided by lunar observers sparse in all the world. Another collaboration has also been started with the Lunar Section’s of [http://www.baalunarsection.org.uk/tlp.htm British Astronomical Association] (BAA) and the american [http://alpo-astronomy.org/ Association Lunar & Planetary Observer] (ALPO).<br>The UAI Lunar Section had collaboration, in the period November 2013 – April 2014, with [http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/ladee/main/index.html NASA | + | <br>This is new programme that has been started by the Lunar Section Research of Unione Astrofili Italiani (UAI), and consists of monitoring the Moon’s night side for Impact flashes that occur when meteoroids, in the Solar System, strike the lunar surface at high velocity. The research on Lunar Impacts started only recently, when on November 18, 1999, the orbit of the Earth-Moon system intersected the Leonids meteor shower orbit. On that date, Brian Cudnik was the first person to observe this phenomena visually, through his telescope, i.e. the flash of light when one object in the solar system collides with the surface of another, and this event was confirmed, and recorded on video, by other independent lunar observers. After this first impact flash, there followed in succession six other impact flashes, always confirmed by independent observers, and this opened up a new scientific way to carry out research into impact rates on our natural satellite. This type of programme is important scientifically for a number of reasons, for example if we measure the brightness of the flash and compare it to that of stars near to the limb of the Moon, then we can obtain the magnitude of the flash, and from this determine the emitted energy of the impact. If the meteoroid is from a known shower, and of known velocity, then its mass can be calculated too.<br> This study can be very useful in detemining the quantity of “minor bodies” that pass near to the Earth, and to calibrate this with other methods, for example meteor/meteorite rates detected in the Earth’s atmosphere. The programme could have a really important scientific significance for future lunar exploration too, i.e. to be able to know the present day lunar impact rate and how this varies across the lunar surface would be essential to know about in the design of future lunar bases, and also where they should be situated, in order to minimize impact damage. <br><br>The mass of meteoroids that fall on lunar surface can vary between some tens of grams and many hundreds of kilograms, while the velocity of impact is between 20 and 72 km/second. These meteoroids can originate from cometary showers that periodically cross the orbit of the Earth-Moon system, or from asteroidal bodies that are more sporadic in nature, and it is this second case that the mass of meteoroids have more significance to the safe design of lunar bases. In the instance immediately after an impact, less than one percent of the total kinetic energy released from the impact, is transformed into visible light that Earth based observers can see in the form of short flashes. These flashes can last from typically less than 1/10th of a second to very occasionally a few seconds for the largest bodies to hit the Moon. After the impact the meteoroid disintegrates and a new, metre scale, crater forms. <br>The UAI Lunar Section undertakes this research programme in collaboration with the [http://www.nasa.gov/centers/marshall/news/lunar/ NASA Marshall Space Flight Center] who, at professional level, catalogue all observations of Lunar Impacts provided by lunar observers sparse in all the world. Another collaboration has also been started with the Lunar Section’s of [http://www.baalunarsection.org.uk/tlp.htm British Astronomical Association] (BAA) and the american [http://alpo-astronomy.org/ Association Lunar & Planetary Observer] (ALPO).<br>The UAI Lunar Section had collaboration, in the period November 2013 – April 2014, with [http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/ladee/main/index.html NASA's LADEE] mission (Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer) for research into Lunar Impacts. Although this american spacecraft, developed in the NASA’s Research Center of Ames, CA, could not detect impact flashes directly, LADEE’s LDEX instrument was able to detect the possible presence of dust in lunar exosphere. So by comparing impact flashes, detected by Earth-based astronomers, with dust levels in the exosphere, theoretical models of lunar impact lofted dust can be tested/improved.<br>Per poter riprendere gli impatti lunari è necessario osservare la parte di Luna che non è illuminata dal Sole e quindi va monitorata la parte in ombra, ed i periodi favorevoli per poter osservare questi fenomeni sono dal primo giorno dopo la fase di Luna Nuova fino al giorno di Primo Quarto compreso (in questo caso si osserva la parte lunare Ovest che sarà in ombra, ed effettuando le osservazioni principalmente nelle zone più vicine al lembo Ovest, Fig.2), e poi dal giorno di Ultimo Quarto compreso fino al giorno prima della fase di Luna Nuova (in questo caso andrà osservata la parte lunare Est in ombra sempre con la stessa metodologia, Fig.1), questo perchè le zone dove si verificano maggiormente gli impatti sono situate in prossimità dei lembi lunari Ovest ed Est. Le due figure sotto riportate illustrano all'interno di un rettangolo di colore rosso le zone lunari che dovrebbero essere riprese dal sensore della videocamera impiegata per le osservazioni. Oltre alla superficie lunare può essere utile riprendere anche una piccola zona del fondo cielo al di fuori dei lembi lunari come illustrato nelle due figure, questo per avere sempre un punto di riferimento fisso.<br><br> <br> <br> [[Image:Fov ovest 2.jpg|right|400x300px|Fov ovest 2.jpg]] [[Image:Fov est 2.jpg|left|400x300px|Fov est 2.jpg]] <br> <br> <br> <br> |

<div><br></div> | <div><br></div> | ||

<br> <br> <br> <br> | <br> <br> <br> <br> | ||

Versione delle 18:26, 16 giu 2015

The Research, Observation and Recording of Lunar Impacts

This is new programme that has been started by the Lunar Section Research of Unione Astrofili Italiani (UAI), and consists of monitoring the Moon’s night side for Impact flashes that occur when meteoroids, in the Solar System, strike the lunar surface at high velocity. The research on Lunar Impacts started only recently, when on November 18, 1999, the orbit of the Earth-Moon system intersected the Leonids meteor shower orbit. On that date, Brian Cudnik was the first person to observe this phenomena visually, through his telescope, i.e. the flash of light when one object in the solar system collides with the surface of another, and this event was confirmed, and recorded on video, by other independent lunar observers. After this first impact flash, there followed in succession six other impact flashes, always confirmed by independent observers, and this opened up a new scientific way to carry out research into impact rates on our natural satellite. This type of programme is important scientifically for a number of reasons, for example if we measure the brightness of the flash and compare it to that of stars near to the limb of the Moon, then we can obtain the magnitude of the flash, and from this determine the emitted energy of the impact. If the meteoroid is from a known shower, and of known velocity, then its mass can be calculated too.

This study can be very useful in detemining the quantity of “minor bodies” that pass near to the Earth, and to calibrate this with other methods, for example meteor/meteorite rates detected in the Earth’s atmosphere. The programme could have a really important scientific significance for future lunar exploration too, i.e. to be able to know the present day lunar impact rate and how this varies across the lunar surface would be essential to know about in the design of future lunar bases, and also where they should be situated, in order to minimize impact damage.

The mass of meteoroids that fall on lunar surface can vary between some tens of grams and many hundreds of kilograms, while the velocity of impact is between 20 and 72 km/second. These meteoroids can originate from cometary showers that periodically cross the orbit of the Earth-Moon system, or from asteroidal bodies that are more sporadic in nature, and it is this second case that the mass of meteoroids have more significance to the safe design of lunar bases. In the instance immediately after an impact, less than one percent of the total kinetic energy released from the impact, is transformed into visible light that Earth based observers can see in the form of short flashes. These flashes can last from typically less than 1/10th of a second to very occasionally a few seconds for the largest bodies to hit the Moon. After the impact the meteoroid disintegrates and a new, metre scale, crater forms.

The UAI Lunar Section undertakes this research programme in collaboration with the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center who, at professional level, catalogue all observations of Lunar Impacts provided by lunar observers sparse in all the world. Another collaboration has also been started with the Lunar Section’s of British Astronomical Association (BAA) and the american Association Lunar & Planetary Observer (ALPO).

The UAI Lunar Section had collaboration, in the period November 2013 – April 2014, with NASA's LADEE mission (Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer) for research into Lunar Impacts. Although this american spacecraft, developed in the NASA’s Research Center of Ames, CA, could not detect impact flashes directly, LADEE’s LDEX instrument was able to detect the possible presence of dust in lunar exosphere. So by comparing impact flashes, detected by Earth-based astronomers, with dust levels in the exosphere, theoretical models of lunar impact lofted dust can be tested/improved.

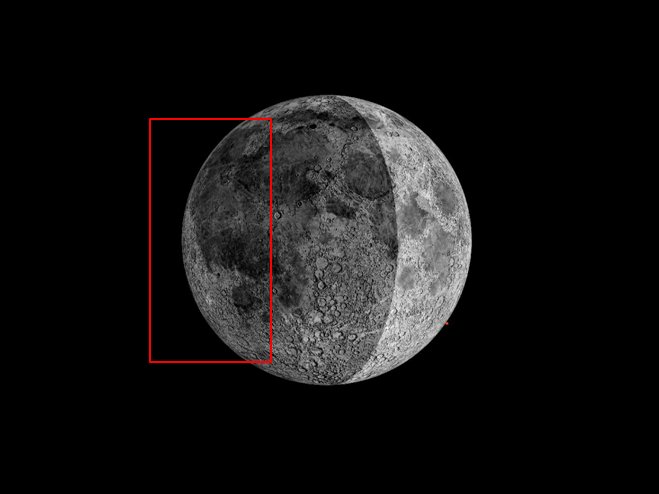

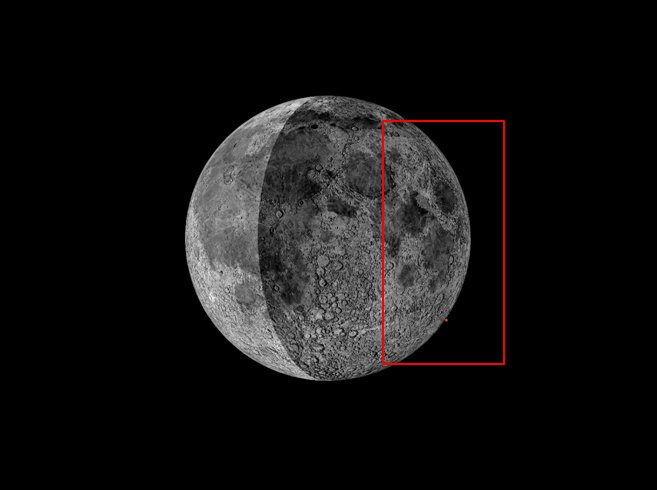

Per poter riprendere gli impatti lunari è necessario osservare la parte di Luna che non è illuminata dal Sole e quindi va monitorata la parte in ombra, ed i periodi favorevoli per poter osservare questi fenomeni sono dal primo giorno dopo la fase di Luna Nuova fino al giorno di Primo Quarto compreso (in questo caso si osserva la parte lunare Ovest che sarà in ombra, ed effettuando le osservazioni principalmente nelle zone più vicine al lembo Ovest, Fig.2), e poi dal giorno di Ultimo Quarto compreso fino al giorno prima della fase di Luna Nuova (in questo caso andrà osservata la parte lunare Est in ombra sempre con la stessa metodologia, Fig.1), questo perchè le zone dove si verificano maggiormente gli impatti sono situate in prossimità dei lembi lunari Ovest ed Est. Le due figure sotto riportate illustrano all'interno di un rettangolo di colore rosso le zone lunari che dovrebbero essere riprese dal sensore della videocamera impiegata per le osservazioni. Oltre alla superficie lunare può essere utile riprendere anche una piccola zona del fondo cielo al di fuori dei lembi lunari come illustrato nelle due figure, questo per avere sempre un punto di riferimento fisso.

Fig.1 - Ripresa del settore lunare Est dopo la fase di Ultimo Quarto Fig.2 - Ripresa del settore lunare Ovest dopo la fase di Luna Nuova

La strumentazione consigliata per la ricerca consiste in una montatura motorizzata che possa inseguire quanto più perfettamente possibile la Luna, (dove prevista inserire la velocità lunare) e come strumento un telescopio avente un diametro di almeno 20 cm (8”) con basso rapporto focale come f/5 o f/3,3 questo per poter riprendere un campo di zona lunare quanto più ampio possibile (Fig.3 e 4) e allo stesso tempo aumentare la luminosità dello strumento.

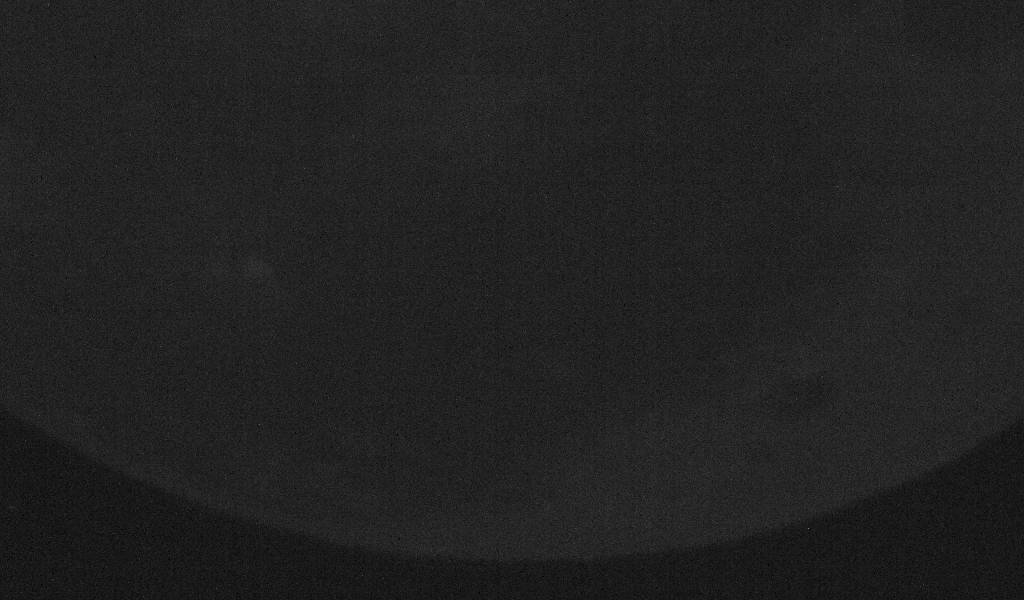

Fig.3 - immagine del lato buio Ovest lunare ripresa con newton 1000/200 ad f/5 e videocamera ASI 120MM da Bruno Cantarella (AL)

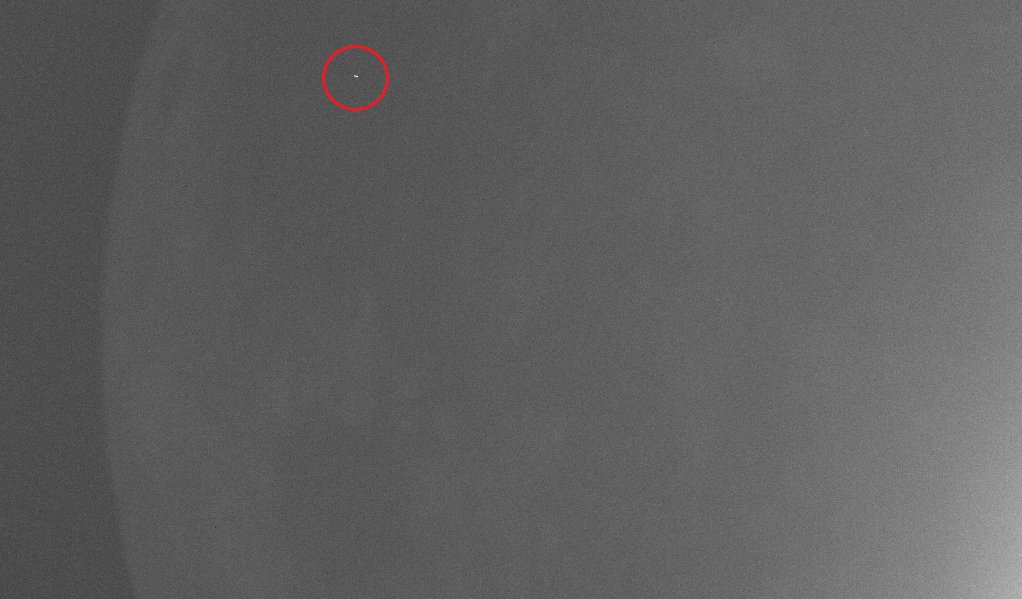

Come apparecchi di ripresa dedicati possono essere impiegate delle moderne videocamere per astronomia con presa USB di ultima generazione da collegare al proprio computer ad una porta USB 2.0 e che possano produrre dei filmati in file AVI. Le videocamere devono inoltre possedere una buona sensibilità alle basse intensità luminose per poter riprendere con sufficiente contrasto rispetto al fondo cielo la parte in ombra della Luna (la cosidetta luce cinerea), ed è di notevole importanza cercare di riprendere anche quanto più possibile le formazioni sottostanti lunari che sono in ombra con lo scopo di poter individuare la posizione selenografica di un eventuale flash da impatto. Le videocamere vanno impostate con un tempo di esposizione di almeno 0,030 sec (1/30 sec) per poter ottenere una velocità di ripresa (frame rate) di 30 fps (frame per secondo), questo perchè la maggior parte dei flash da impatto hanno una durata media di 1/10 di secondo, e quindi è importante registrare il candidato flash da impatto almeno in 2 o 3 frame consecutivi per registrare dopo l'intensità di picco del flash anche la diminuizione dell’intensità luminosa in funzione del tempo. Inoltre è di fondamentale importanza che il sospetto flash da impatto resti sempre fisso nella stessa posizione in tutti i frame in cui esso compare, cioè in pratica il flash deve accendere sempre gli stessi pixel del sensore dell’apparecchio di ripresa usato. Molto spesso vengono ripresi dei fenomeni che possono sembrare simili a dei flash da impatto ma che invece sono semplicemente dei raggi cosmici temporanei che appaiono e scompaiono in tempi rapidissimi ma che lasciano comunque una traccia sul sensore e quindi sono visibili solo in un frame (Fig.5 e 6). Inoltre durante le riprese è possibile riprendere anche dei satelliti artificiali terrestri che attraversano il disco lunare, ed in questo caso essi si presentano come delle striscie luminose molto veloci (Fig.7), oppure anche come dei punti luminosi simili ad un flash ma che si spostano attraverso il campo lunare ripreso per poi scomparire. Per poter verificare se il fenomeno ripreso è un satellite artificiale è possibile consultare il sito web di Heavens–Above oppure quello di Calsky. Il Marshall Space Flight Center della NASA ha stabilito delle condizioni precise perchè un candidato flash da impatto registrato da un osservatore lunare possa essere considerato come un reale impatto lunare, per maggiori informazioni cliccare qui

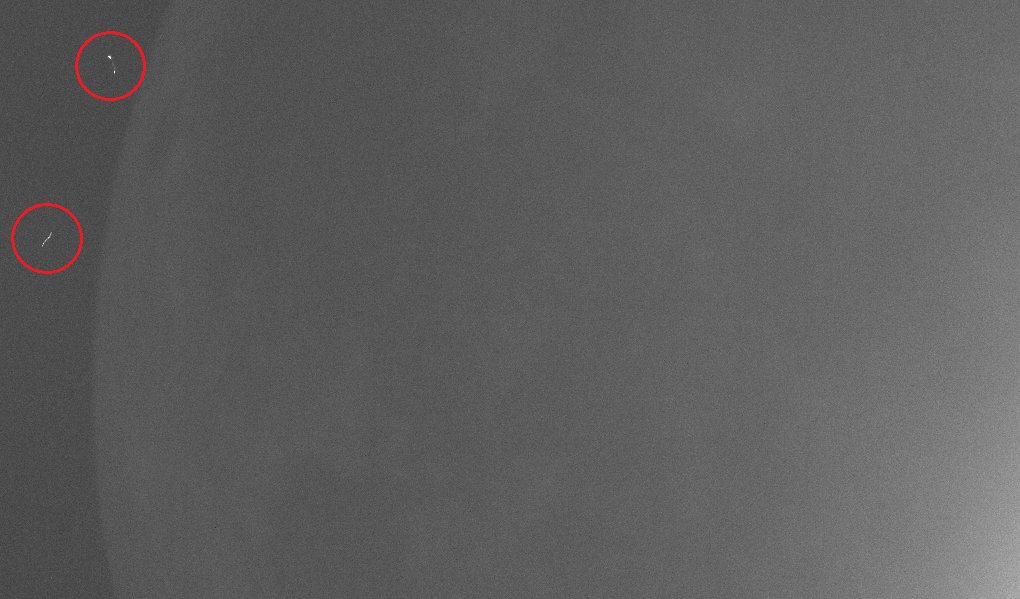

Fig.5 - Probabile raggio cosmico ripreso dalla videocamera (indicato dal cerchio rosso), immagine di Antonio Mercatali (LI)

Fig.6 - Anche in questa immagine ci sono dei probabili raggi cosmici (sempre indicati dai cerchi rossi), immagine di Antonio Mercatali (LI)

Fig. 7 - Il satellite cinese HJ-1C ripreso da Bruno Cantarella (Melazzo, AL) il 25/1/2015 alle ore 17:50:38 T.U. mentre attraversa il disco lunare. Verifica effettuata da Aldo Tonon (TO) dal sito Heavens-Above

Eventuali registrazioni di potenziali flash da impatto e/o report osservativi visuali possono essere inviati all'indirizzo della Sezione Luna luna@uai.it in forma di immagini JPEG e in formato pdf per i rapporti osservativi visuali, i quali però dovranno essere sempre in entrambi i casi completi della data ed orario in Tempo Universale (T.U.) del momento in cui si è osservato e/o registrato il fenomeno.

Il Coordinatore del progetto è Antonio Mercatali.

Orari per l'osservazione per il mese di Giugno 2015

Luna in fase calante, osservazione del lembo buio Est con inizio delle osservazioni dal sorgere della Luna e fino all’arrivo della luce dell’alba:

- 9 la Luna sorge alle ore 23:04 T.U. del giorno 8

- 10 “ alle ore 23:39 T.U. del giorno 9

- 11 “ alle ore 00:14 T.U.

- 12 “ alle ore 00.49 T.U.

- 13 “ alle ore 01:27 T.U.

- 14 “ alle ore 02:08 T.U.

- 15 “ alle ore 02:53 T.U.

Luna in fase crescente, osservazione del lembo buio Ovest con inizio delle osservazioni da quando fa buio e fino al tramonto della Luna:

- 17 la Luna tramonta alle ore 19:24 T.U.

- 18 “ alle ore 20:09 T.U.

- 19 “ alle ore 20.49 T.U.

- 20 “ alle ore 21.24 T.U.

- 21 “ alle ore 21.55 T.U.

- 22 “ alle ore 22:25 T.U.

- 23 “ alle ore 22.53 T.U.

- 24 “ alle ore 23:21 T.U.

Sezione di Ricerca Luna