Lunar Impacts Research

| Riga 11: | Riga 11: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

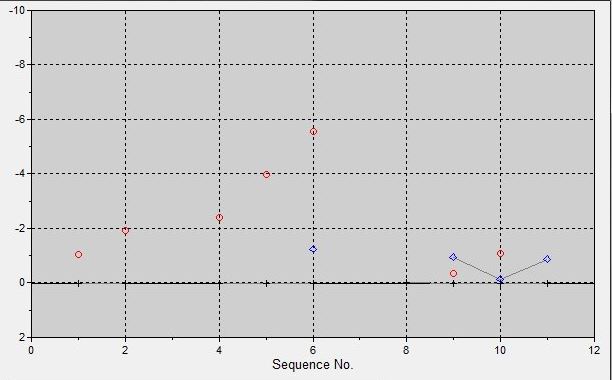

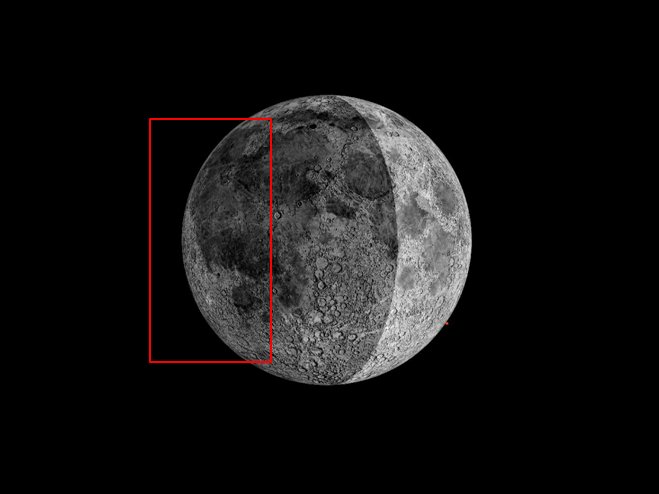

| − | On 12 March 2016 at 18h 33m 02s UT the members of Section Bruno Cantarella and Luigi Zanatta (Melazzo, AL, Italy, 44°39'25" North, 8°25'52" East) has recorded the first flash of impact of one meteoroid on the Lunar surface. The observation and the record has been made with one | + | On 12 March 2016 at 18h 33m 02s UT the members of Section Bruno Cantarella and Luigi Zanatta (Melazzo, AL, Italy, 44°39'25" North, 8°25'52" East) has recorded the first flash of impact of one meteoroid on the Lunar surface. The observation and the record has been made with one unique Newton telescope 200/1000 at f/5 with astronomical videocamera ZWO mod. ASI 120MM with a frame rate of 25 fps and image's resolution of 1024 X 600. Currently the Candidate Impact has been not confirmed by others indepedents observers. After the send of observatives data by the Lunar Impacts Project's Coordinator to NASA's Marshall Space Fligth Center, the American Team has valued in positive mode the obtained result and has classified the flash as Candidate Lunar Impact n° 28 in the list of Independent Observers. Also has been made by Dott. Alessandro Marchini Responsible of Astronomical Observatory of the University of Siena (Italy) a first light curve of impact flash that at the moment of the luminosity peak has been 250 units more bright than lunar surface around at the impact zone. The phenomenon it is lasted 0.08 seconds (1/12 sec.), and the impact zone has been detected at the selenographics coordinates of 39.9° West and 8.0° South +/-0.2°, in the southern zone of Oceanus Procellarum, and more precisely to South-West of the crater Wichmann B. |

<br> | <br> | ||

Versione delle 18:52, 5 lug 2016

First Candidate Lunar Impact record by SdR Luna UAI

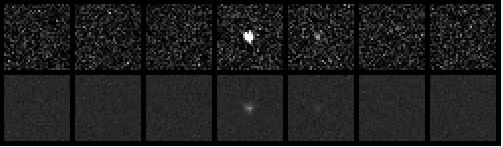

In the animated image it is visible the sequence of impact flash, with the peak in the frame 2 and in decreasing luminosity in the frame 3

On 12 March 2016 at 18h 33m 02s UT the members of Section Bruno Cantarella and Luigi Zanatta (Melazzo, AL, Italy, 44°39'25" North, 8°25'52" East) has recorded the first flash of impact of one meteoroid on the Lunar surface. The observation and the record has been made with one unique Newton telescope 200/1000 at f/5 with astronomical videocamera ZWO mod. ASI 120MM with a frame rate of 25 fps and image's resolution of 1024 X 600. Currently the Candidate Impact has been not confirmed by others indepedents observers. After the send of observatives data by the Lunar Impacts Project's Coordinator to NASA's Marshall Space Fligth Center, the American Team has valued in positive mode the obtained result and has classified the flash as Candidate Lunar Impact n° 28 in the list of Independent Observers. Also has been made by Dott. Alessandro Marchini Responsible of Astronomical Observatory of the University of Siena (Italy) a first light curve of impact flash that at the moment of the luminosity peak has been 250 units more bright than lunar surface around at the impact zone. The phenomenon it is lasted 0.08 seconds (1/12 sec.), and the impact zone has been detected at the selenographics coordinates of 39.9° West and 8.0° South +/-0.2°, in the southern zone of Oceanus Procellarum, and more precisely to South-West of the crater Wichmann B.

The sequence of the impact flash obtained with analysis software LunarScan 2.00

The light curve of the flash obtained with MaxIm DL5 software

The Research, Observation and Recording of Lunar Impacts

This is new programme that has been started by the Lunar Section Research of Unione Astrofili Italiani (UAI), and consists of monitoring the Moon’s night side for Impact flashes that occur when meteoroids, in the Solar System, strike the lunar surface at high velocity. The research on Lunar Impacts started only recently, when on November 18, 1999, the orbit of the Earth-Moon system intersected the Leonids meteor shower orbit. On that date, Brian Cudnik was the first person to observe this phenomena visually, through his telescope, i.e. the flash of light when one object in the solar system collides with the surface of another, and this event was confirmed, and recorded on video, by other independent lunar observers. After this first impact flash, there followed in succession six other impact flashes, always confirmed by independent observers, and this opened up a new scientific way to carry out research into impact rates on our natural satellite. This type of programme is important scientifically for a number of reasons, for example if we measure the brightness of the flash and compare it to that of stars near to the limb of the Moon, then we can obtain the magnitude of the flash, and from this determine the emitted energy of the impact. If the meteoroid is from a known shower, and of known velocity, then its mass can be calculated too.

This study can be very useful in detemining the quantity of “minor bodies” that pass near to the Earth, and to calibrate this with other methods, for example meteor/meteorite rates detected in the Earth’s atmosphere. The programme could have a really important scientific significance for future lunar exploration too, i.e. to be able to know the present day lunar impact rate and how this varies across the lunar surface would be essential to know about in the design of future lunar bases, and also where they should be situated, in order to minimize impact damage.

The mass of meteoroids that fall on lunar surface can vary between some tens of grams and 10 - 20 kilograms about, while the velocity of impact is between 20 and 72 km/second. These meteoroids can originate from cometary showers that periodically cross the orbit of the Earth-Moon system, or from asteroidal bodies that are more sporadic in nature, and it is this second case that the mass of meteoroids have more significance to the safe design of lunar bases. In the instance immediately after an impact, less than one percent of the total kinetic energy released from the impact, is transformed into visible light that Earth based observers can see in the form of short flashes. These flashes can last from typically less than 1/10th of a second to very occasionally a few seconds for the largest bodies to hit the Moon. After the impact the meteoroid disintegrates and a new, metre scale, crater forms.

The UAI Lunar Section undertakes this research programme in collaboration with the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center who, at professional level, catalogue all observations of Lunar Impacts provided by lunar observers sparse in all the world. Another collaboration has also been started with the Lunar Section’s of British Astronomical Association (BAA) and the american Association Lunar & Planetary Observer (ALPO).

The UAI Lunar Section had collaboration, in the period November 2013 – April 2014, with NASA's LADEE mission (Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer) for research into Lunar Impacts. Although this american spacecraft, developed in the NASA’s Research Center of Ames, CA, could not detect impact flashes directly, LADEE’s LDEX instrument was able to detect the possible presence of dust in lunar exosphere. So by comparing impact flashes, detected by Earth-based astronomers, with dust levels in the exosphere, theoretical models of lunar impact lofted dust can be tested/improved.

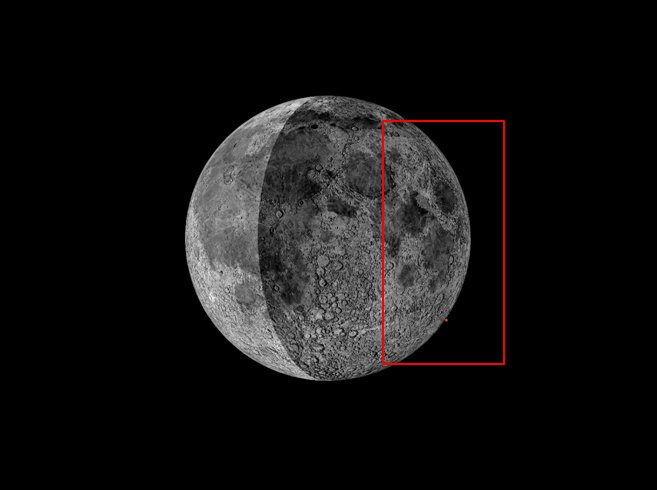

Fig.1 - Take of East edge after the phase of Last Quarter Fig.2 - Take of West edge after the phase of New Moon

The ideal instrumentation for the research of Lunar Impacts is a telescope with a motorized mount (both axes) that can to follow the Moon as perfectly as possible (where it is possible to select tracking rate at lunar velocity). The telescope aperture should have a diameter of at least 8”, with a small focal ratio, e.g. f/5 or f/3.3, - this is to enable a sufficiently large lunar field of view, (Fig.3 e 4) and at the same time to increase the sensitivity of the telescope-camera system.

Fig.3 - Image of earthshine West edge take with newton telescope 1000/200 at f/5 and videocamera ASI 120MM by Bruno Cantarella (AL)

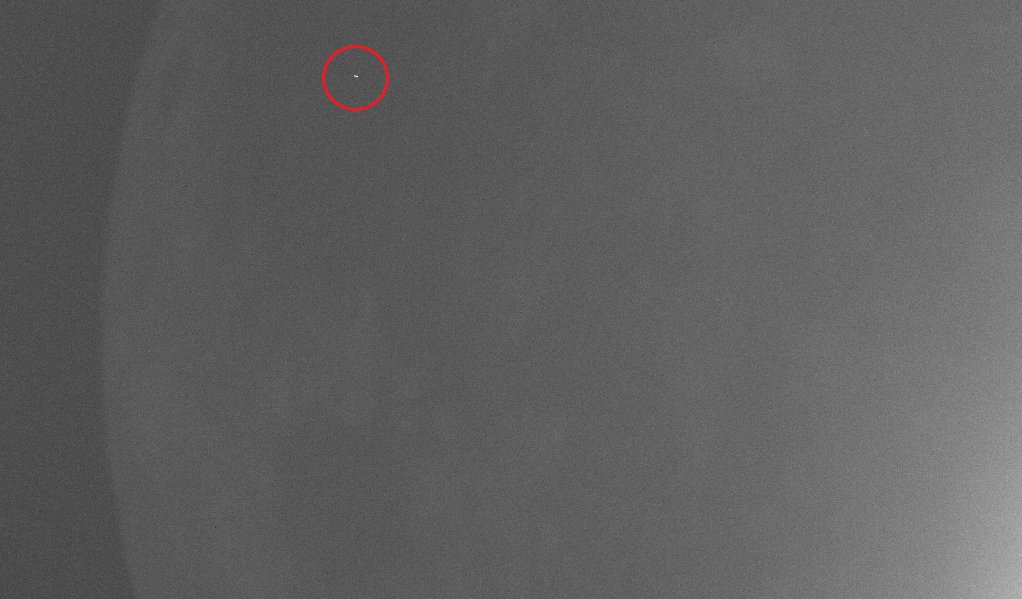

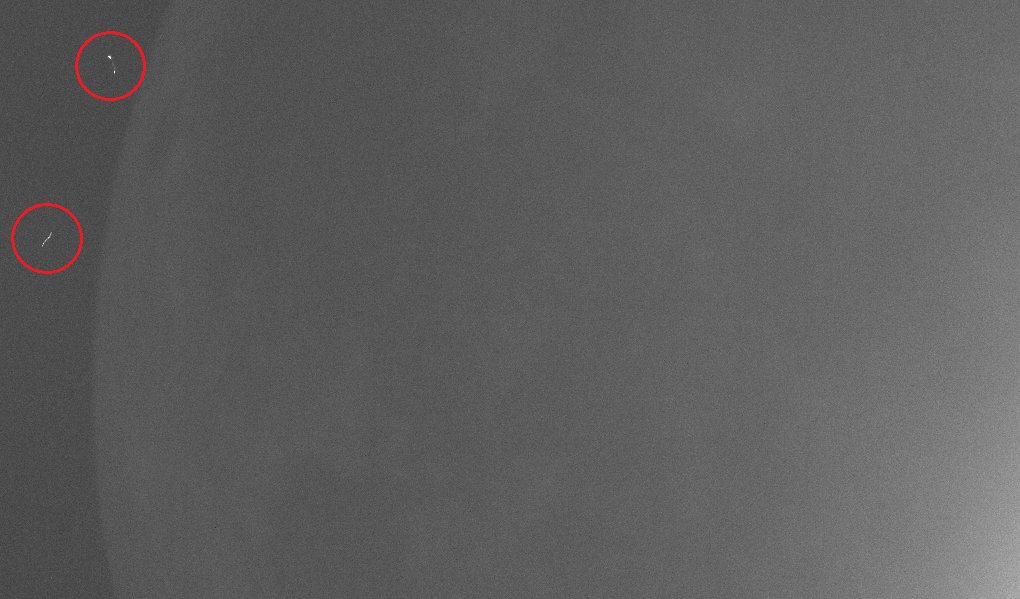

Suggested apparatus for video capture can include modern astronomical video cameras, with USB connections to a computer, however they must be capable of recording video filmed in AVI file format. These videocameras must also have a good sensitivity at low light levels, such that there is sufficient contrast between the sky background, and the night (earthlit) side of the Moon. The camera sensitivity must be able to discern at least some recognizable features in Earthshine too, for the purpose of being able to detemine the map coordinates of the possible impact flashes. The time of each exposure should be set at shorter than 0.033 seconds (1/30 sec) if working at a frame rate of 30 fps; this is necessary because large numbers of lunar impacts have a flash durations of less than 1/10 sec, and so therefore it is important to record suspect flash impact flashes in at least two or three consecutive frames, and to be able to record both the flash luminosity peak as well as the decay of light curve as a function of time. Also it is of fundamental importance that the impact flash remains always fixed in the same position in all frames where it is visible, i.e. the flash must always light the same pixels of the sensor of the astronomical video camera used – so a tracking telescope is recommended. Not all candidate flashes seen are due to real impacts, the majority of flashes detected are in fact the result of cosmic rays air shower particles, that strike the camera, and appear and disappear in a very short time. However these cosmic rays usually create very bright points (and tracks) on the sensor and are visible in only one frame (Fig. 5 and 6). Also during the taking of video some terrestrial satellites can cross the lunar disk, and in this case they can appear as motion blurred streaks (Fig.7), or the slower ones appear as a moving bright spots across the lunar field. One way to check for satellites is to consult the web site of Heavens–Above or Calsky. NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center developed some criteria for classifying the quality of candidate impact flash observations, for more information click here.

Fig.5 - Probable cosmic ray take from videocamera (indicate from a red circle), image by Antonio Mercatali (LI)

Fig.6 - In this image too there are probables cosmics rays (indicate always from reds circles), image by Antonio Mercatali (LI)

Fig. 7 - The chinese artificial satellite HJ-1C take by Bruno Cantarella (Melazzo, AL) on 1/25/2015 at 17:50:38 UT while crossed the lunar disk. Check made by Aldo Tonon (TO) from Heavens-Above website

Captured image frames of candidate impact flashes, or any visual sightings, should be sent to the following e-mail address of the UAI Lunar Section luna@uai.it as JPEG images, or in PDF format for the visual observational reports. Please make sure that you always include the date and the time in UT for the suspected impact flash.

Many thanks to Dr Anthony Cook, Department of Physics, Aberystwyth University for the english revision of this page.

The project’s coordinator is Antonio Mercatali.

Dates and times for observation for July 2016

Moon in decreasing phase, observation of East edge earthshine with start of observations from moonrise to twilight:

- day 1 the Moon rise at 01:12 UT

- day 2 the Moon rise at 01:59 UT

- day 3 the Moon rise at 02:51 UT

Moon in increasing phase, observation of West edge earthshine with start of observations from twilight to moonset:

- day 5 the Moon set at 19:29 UT

- day 6 the Moon set at 20:11 UT

- day 7 the Moon set at 20:48 UT

- day 8 the Moon set at 21:21 UT

- day 9 the Moon set at 21:51 UT

- day 10 the Moon set at 22:20 UT

- day 11 the Moon set at 22:48 UT

- day 12 the Moon set at 23:18 UT

Moon in decreasing phase, observation of East edge earthshine with start of observations from moonrise to twilight:

- day 27 the Moon rise at 22:32 UT of day 26

- day 28 the Moon rise at 23:11 UT of day 27

- day 29 the Moon rise at 23:55 UT of day 28

- day 30 the Moon rise at 00:43 UT

- day 31 the Moon rise at 01:37 UT

Sezione di Ricerca Luna